Stepped out of a Dream

Theodora Sutton

Thursday 9 June 2011

Tuesday 24 May 2011

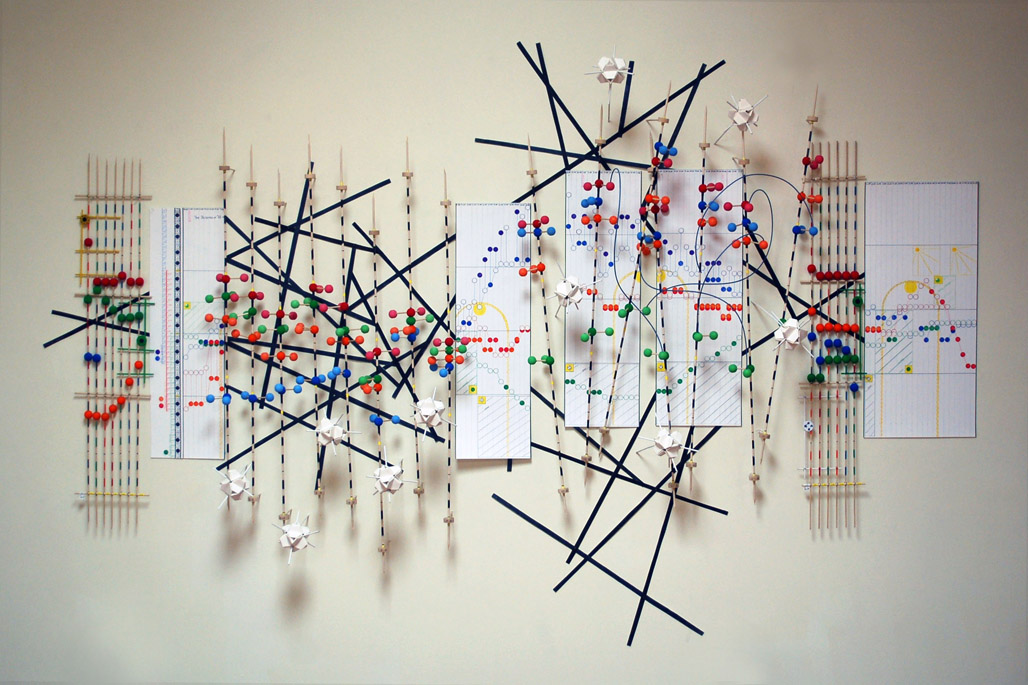

Universe in a Box

Artist Statement

Carl Sagan was best known for being a communicator of science. He spent his life bringing science to the people, with his books and with his Cosmos television program, which transformed previously static data into colloquial, visual, and accessible forms which captured the world's imagination.

"The art and animation we created for Cosmos had to enhance and support Carl's style of presentation and be, like his words, accurate and yet accessible, rigorous, and at the same time stirring." Carl Sagan's Universe, by Yervant Terzian

I see a parallel between the work of people like Sagan and data visualisation as each strive to do the same thing, in framing otherwise unreachable, ephemeral or hugely important pieces of information.

I think visual arrangements of ideas can determine and shape how we perceive them to a huge degree.

"It is not from space that I must seek my dignity, but from the government of my thought. I shall have no more if I possess worlds. By space the universe encompasses and swallows me up like an atom; by thought I comprehend the world." Blaise Pascal, Pensees.

A heart monitor displays a human heartbeat as a single line. The image is iconic and globally understood, but the information about what is actually happening inside the body has been hugely simplified. What if there were a heart monitor that displayed the same information in a different shape, using a different sense, or perhaps even using a different medium? This is a crude example of how in the medical world, a visualisation can change the entire way people think about something.

My work has from the beginning been an attempt to convey to other people my obsession with the cosmic perspective. The ultimate goal for me would be to create an artwork that fulfilled the role of using information to change a person's perspective on how we fit into the cosmic arena.

Although my initial idea for the box was inspired by a computer simulation of the universe, I wanted to use something further removed from space to gather my data from. The sculpture was being made on a human scale, and so human numbers were more appropriate than the 'billions and billions' found in astronomical data.

The box is made of three axis, the 26 letters of the alphabet, the 26 rounded amounts for their occurrence on a page, all done 26 times in series - 26,000 is the number of light years between our Sun and the centre of our galaxy, the Milky Way.

I felt it was apt to collect data from Sagan's 'Cosmos' book because it was one of the things that first inspired be at the beginning of this project.

The insignificance of the action of tallying every letter of the alphabet for the 26 pages that I chose to represent corresponds to Sagan's message that the human life is nothing on the cosmic scale.

"Compared to a star, we are like mayflies, fleeting ephemeral creatures who live out their whole lives in the course of a single day. From the point of view of a mayfly, human beings are stolid, boring, almost entirely immovable, offering hardly a hint that they ever do anything. From the point of a view of a star, a human being is a tiny flash, one of billions of brief lives flickering tenuously on the surface of a strangely cold, anomalously solid, exotically remote sphere of silicate and iron." Cosmos, page 240.

The collection of the data itself felt for me like a performance stretched over a period of time where I essentially read each page 26 times, once for each letter that I was counting. It felt like a vain attempt to take in the messages of the book which can never be fully realised.

It reminded me of the ideas in the theory of Materiality, where I had to go through a slow process which gave me the opportunity to understand what I was doing.

Whereas in 'Dozens and Dozens' I wanted the audience to react emotionally, like a James Turrell piece, this is more of an intellectual idea. It has the gravitas of real information. Giving myself the boundaries imposed by using data instead of creating a visual likeness purely on aesthetic grounds, and so in a sense, like the main artists in Systems Art, I handed over my artistic input to the data.

It was impossible for me to gain the degree of accuracy that I would have liked in the 3D graph. I was forced to use a certain amount of artistic license, although if I had access to more appropriate materials I believe something similar would be possible, perhaps on a bigger scale. For me though the box sits somewhere between data visualisation and sculpture.

"Some scientific art seems like the visual equivalent of the scientific paper, but sometimes they can be poems too." Carl Sagan's Universe, by Yervant Terzian

Carl Sagan was best known for being a communicator of science. He spent his life bringing science to the people, with his books and with his Cosmos television program, which transformed previously static data into colloquial, visual, and accessible forms which captured the world's imagination.

"The art and animation we created for Cosmos had to enhance and support Carl's style of presentation and be, like his words, accurate and yet accessible, rigorous, and at the same time stirring." Carl Sagan's Universe, by Yervant Terzian

I see a parallel between the work of people like Sagan and data visualisation as each strive to do the same thing, in framing otherwise unreachable, ephemeral or hugely important pieces of information.

I think visual arrangements of ideas can determine and shape how we perceive them to a huge degree.

"It is not from space that I must seek my dignity, but from the government of my thought. I shall have no more if I possess worlds. By space the universe encompasses and swallows me up like an atom; by thought I comprehend the world." Blaise Pascal, Pensees.

A heart monitor displays a human heartbeat as a single line. The image is iconic and globally understood, but the information about what is actually happening inside the body has been hugely simplified. What if there were a heart monitor that displayed the same information in a different shape, using a different sense, or perhaps even using a different medium? This is a crude example of how in the medical world, a visualisation can change the entire way people think about something.

My work has from the beginning been an attempt to convey to other people my obsession with the cosmic perspective. The ultimate goal for me would be to create an artwork that fulfilled the role of using information to change a person's perspective on how we fit into the cosmic arena.

Although my initial idea for the box was inspired by a computer simulation of the universe, I wanted to use something further removed from space to gather my data from. The sculpture was being made on a human scale, and so human numbers were more appropriate than the 'billions and billions' found in astronomical data.

The box is made of three axis, the 26 letters of the alphabet, the 26 rounded amounts for their occurrence on a page, all done 26 times in series - 26,000 is the number of light years between our Sun and the centre of our galaxy, the Milky Way.

I felt it was apt to collect data from Sagan's 'Cosmos' book because it was one of the things that first inspired be at the beginning of this project.

The insignificance of the action of tallying every letter of the alphabet for the 26 pages that I chose to represent corresponds to Sagan's message that the human life is nothing on the cosmic scale.

"Compared to a star, we are like mayflies, fleeting ephemeral creatures who live out their whole lives in the course of a single day. From the point of view of a mayfly, human beings are stolid, boring, almost entirely immovable, offering hardly a hint that they ever do anything. From the point of a view of a star, a human being is a tiny flash, one of billions of brief lives flickering tenuously on the surface of a strangely cold, anomalously solid, exotically remote sphere of silicate and iron." Cosmos, page 240.

The collection of the data itself felt for me like a performance stretched over a period of time where I essentially read each page 26 times, once for each letter that I was counting. It felt like a vain attempt to take in the messages of the book which can never be fully realised.

It reminded me of the ideas in the theory of Materiality, where I had to go through a slow process which gave me the opportunity to understand what I was doing.

Whereas in 'Dozens and Dozens' I wanted the audience to react emotionally, like a James Turrell piece, this is more of an intellectual idea. It has the gravitas of real information. Giving myself the boundaries imposed by using data instead of creating a visual likeness purely on aesthetic grounds, and so in a sense, like the main artists in Systems Art, I handed over my artistic input to the data.

It was impossible for me to gain the degree of accuracy that I would have liked in the 3D graph. I was forced to use a certain amount of artistic license, although if I had access to more appropriate materials I believe something similar would be possible, perhaps on a bigger scale. For me though the box sits somewhere between data visualisation and sculpture.

"Some scientific art seems like the visual equivalent of the scientific paper, but sometimes they can be poems too." Carl Sagan's Universe, by Yervant Terzian

Quotes from Data Flow

"Visual metaphors are a powerful aid to human thinking. From Sanskrit through hieroglyphics to the modern alphabet, we have used ciphers, objects, and illustrations to share meaning with other people, thus enabling collective and collaborative thought. As our experience of the world has become more complex and nuanced, the demands to our thinking aids have increased proportionally. Diagrams, data graphics, and visual confections have become the language we resort to in this abstract and complex world. They help us understand, create, and completely experience reality."

"The information designer shapes an experience, or view, of the data with a particular aim in mind."

"When the aim is to inform, data has to be subjected to editorial interpretation before a design is generated. If you skip this step, the infographic will turn out to be an exact reproduction of the raw data. We like our working process to be visible - probably out of an urge to be accountable. BUt whatever the reason, it should never be a process for the process' sake; rather, it should be an aid in creating an image that tells a certain story."Catalogtree interview

"Visual metaphors are a powerful aid to human thinking. From Sanskrit through hieroglyphics to the modern alphabet, we have used ciphers, objects, and illustrations to share meaning with other people, thus enabling collective and collaborative thought. As our experience of the world has become more complex and nuanced, the demands to our thinking aids have increased proportionally. Diagrams, data graphics, and visual confections have become the language we resort to in this abstract and complex world. They help us understand, create, and completely experience reality."

"The information designer shapes an experience, or view, of the data with a particular aim in mind."

"When the aim is to inform, data has to be subjected to editorial interpretation before a design is generated. If you skip this step, the infographic will turn out to be an exact reproduction of the raw data. We like our working process to be visible - probably out of an urge to be accountable. BUt whatever the reason, it should never be a process for the process' sake; rather, it should be an aid in creating an image that tells a certain story."Catalogtree interview

Building the Box

My practice cube had actually been slightly more of a rectangle because the pieces I made it with were not purpose cut.

.

Another thing that I realised from the test cube was that it was ideal to wrap the thread around the edges of the box, however this didn't matter on the practice as I was using fishing wire - in the final design I was using black thread on white wood.

I considered stapling the wood to the insides of the wood but the wood was going to be too frail. I decided to wrap on the outside edges and cover over them with white coving to achieve the cleanest finish

The LEDs are proving tricky, I had assumed I could gluegun them together and dip them in black metal paint but this ended up making them flicker and turn off. Whether it was the heat of the glue, the paint ruining the circuit or what, I've had to go with black tape again. I can still use the paint to touch up the edges though.

I realised I had to use something stronger than ordinary thread. I didn't want to use nylon thread because of its reflective quality so I decided to spray paint it black once it was threaded up.

I feel like LEDs have a magical quality, like they are the modern equivalent of candlelight and that they bring a certain romanticising effect - which is relevant for me because I find a lot of my interest in science is based on a romanticisation of otherwise static scientific information.

I decided to put white beading on the edges of the box to cover over the string that I had wrapped around the wood, and to give it the white exterior of that Universe Simulation that originally inspired the piece.

Systems Art

"Information presented at the right time and in the right place can potentially be very powerful. It can affect the general social fabric ... The working premise is to think in terms of systems: the production of systems, the interface with and the exposure of existing systems ... Systems can be physical, biological, or social."- Hans Haacke’s response (1971) to the cancelling of Haacke’s show at the Guggenheim. Quoted in Lucy Lippard, Six Years: the Dematerialization of the Art Object 1966–1972 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997 [1974]) p. xiii.

"[The] cultural obsession with the art object is slowly disappearing and being replaced by what might be called ‘systems consciousness’. Actually, this shifts from the direct shaping of matter to a concern for organizing quantities of energy and information." Jack Burnham, Beyond Modern Sculpture (1968)

Systemic art is used to "describe a type of abstract art characterized by the use of very simple standardized forms, usually geometric in character, either in a single concentrated image or repeated in a system arranged according to a clearly visible principle of organization" Lawrence Alloway, Systemic art." The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Ed. Ian Chilvers.

Susanne Treister

http://ensemble.va.com.au/Treister/ScifiKTL/SciFiKabbalaTL.html

"In A Timeline of Science Fiction Inventions: Weapons, Warfare and Security Treister has drawn up a history documenting innovations of imaginary and fantastic military technology. These include the 'Raytron Apparatus', a form of aerial surveillance, which was described in 'Beyond the Stars' by Ray Cummings in 1928, or the 'Control Helmet', from 'Easy Money' by Edward Hamilton in 1934. The timeline starts in 1726 with the 'Knowledge Engine' in Gulliver's travels and carries on up to the present day. It allows us to see the meetings of worlds as these weapons sometimes travel from the fantastic to manifest themselves into the real, like the 'Atomic Bomb' described in 'The Crack of Doom' by Robert Cromie in 1895. The format in which she organises this information is the schema of the connected circles of the tree of life or the Sephirot, from the Jewish mystical traditions of the Kabbalah, a representation of linkages between the worlds above and the physical world below and which map stages of transformation between these realms.

The formal beauty of these geometries of information reminds us of the hermetic histories of Twentieth Century Abstraction, how it shared the intention to seek the hidden truths that lay beyond or behind everyday appearances. This desire linked mystics such as Hilma Af Klint (who in turn drew on references and symbols that the Alchemists themselves would have recognised) to artists like Kandinsky, Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, Robert Delaunay and Brancusi and their transformative Theosophical dreams. The belief that art could change the objective conditions of human life requires similar transformations to those that captivated the alchemists: What is real is not the external form, but the essence of things,' wrote Brancusi. 'It is impossible for anyone to express anything essentially real by imitating its exterior surface.' Perhaps, disturbingly, Treister is showing us the world that has emerged in spite of - or perhaps because of - these dizzying intentions."

- Excerpt from catalogue essay by Richard Grayson, published by Annely Juda Fine Art, London September 2008

Future Everything Exhibition

Data is the evidence, the trace of everything that has past, a slice of time which once was, and it is changing our future.

Artists have always sought to give form to human experience that is beyond the everyday. In data, they have a rich resource with which to work. Art can make data tangible, it can bring it alive, real its hidden beauty, and illustrate the ways it can be exploited, and how it can shape our daily lives.

In the coming years, FutureEverything will be commissioning artists and designers to help build an open data future. We are commissioning leading artists to create the new ways of seeing we will need in open data environments, to build an open data imaginary, a new conceptual and visual language.

http://futureeverything.org/

"The Data Dimension at FutureEverything 2011 (Manchester, UK) features an eclectic mix of design and art projects which gesture towards a data-driven culture. The first microscope was designed by Galileo Galilei (1564–1642). The microscope, like the telescope, revealed entirely new worlds, at scales impossible for humans to perceive. Today, like their predecessor, scientists, artists, academics and amateurs, re-purpose, extend, and invent new technologies to observe and comprehend the things no one has seen or understood before. This not only reveals a previously unimagined realm, more than this it constructs a new reality, giving shape and life to a new dimension. The artworks featured in The Data Dimension are an example of the type of experiments taking place. They are spyglasses to study the microscopic, immaterial and infinitely complex. This is about illuminating a future, and creating a new perspective, on a world that is only beginning to emerge. The Data Dimension presents a selection of these Digital Microscopes; artworks that nurture new insights into the invisible infrastructures that make up our world. Here designers and artists visualise the invisible layer of complex data that surrounds our daily lives, making data come alive.

It is possible to imagine a future where data really is without boundaries and it shapes the physical world around us."

Iohanna Panni

Nathalie Miebach

http://rhizome.org/editorial/2011/may/6/data-dimension-futureeverything-2011/

Systems Art - Hughes and Steele

Systems art

The ideas within Systems Art in terms of the Systems Group, founded by Malcolm Hughes and Jeffrey Steele in around 1970, were mainly evoked through painting.

The ideas within Systems Art in terms of the Systems Group, founded by Malcolm Hughes and Jeffrey Steele in around 1970, were mainly evoked through painting.

"Malcolm Hughes was born in 1920 in Manchester. He studied art in Manchester at the Regional College of Art and at the Royal College of Art. During his 30s he was influenced by British abstract artists, but by the early 1960s he began to develop his own Constructivist practice. This type of art first developed in Russia at the start of the twentieth century, and was to become a truly international art form over the following decades. It does not seek to represent what can be seen in the visual world, but to construct works from standard elements and rules. It is a rational art that offers both formal and surprisingly sensual results.

In 1969 Hughes co-founded the Systems Group with Jeffrey Steele." http://www.malcolmhughesartist.eu/biography.html

Malcolm Hughes

Jeffrey Steele

Quotes from 'Towards a Rational Aesthetic: Constructive Art in Post-war Britain'

(on Constructivism)

The concept of the non-figurative abstract art work as not

representing or symbolising anything external to itself.

• The key principle of the art work being constructed or built up

from a vocabulary of generally geometric elements, based on

some form of underlying system or structure.

• The work standing for itself, not as an expression of the artist’s

personality.

• An affinity, in terms of its rationality and structural principles,

with science and technology.

• Hard-edged imagery, an absence of illusionistic perspective or

chiaroscuro, and the concept of space as a compositional

element.

• The use of non-traditional and often industrial materials,

particularly in constructed abstract reliefs.

"[Anthony Hill ] described the relationship between art and mathematics in his work in these terms: “The mathematical thematic can only be a component: one is organising something which is itself an object of achievement which is clearly not mathematical,” Put another way, Hill has always been concerned with creating what the critic Andrew Wilson has described as “visual objects which act directly on our senses and in which mathematical structures generate visually satisfying qualities of rhythm, balance and interaction.” Or as Alastair Grieve has written, in an explanation which can be applied to all the artists in this exhibition: “Judgement by eye was always of paramount importance to him, and mathematical systems were only starting points or tools used in the creation of a harmonious object.”"

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)